Out of the night that covers me,

Black as a pit from pole to pole,

I thank whatever gods may be

For my unconquerable soul.

In the fell clutch of circumstance,

I have not winced nor cried aloud.

Under the bludgeonings of chance,

My head is bloody but unbowed.

Beyond this place of wrath and tears

Looms the Horror of the shade,

And yet the menace of the years finds and shall find me unafraid.

It matters not how strait the gate

How charged with punishments the scroll

I am the master of my fate

I am the Captain of my soul."

What does this poem make you think of?

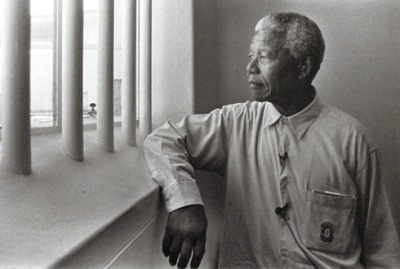

For most, it brings Nelson Mandela to mind. It brings resistance to injustice and defiance of society, prison bars shadowing a face and courage holding the breath of a nation.

President Mandela is a beautiful man. He recited this poem again and again in prison to encourage the inmates and himself. He believed in its words.

But he did not write the words.

Ahh, yes, history hurts. But I think there might hold a pleasant surprise when I tell you who did write it.

For most, it brings Nelson Mandela to mind. It brings resistance to injustice and defiance of society, prison bars shadowing a face and courage holding the breath of a nation.

President Mandela is a beautiful man. He recited this poem again and again in prison to encourage the inmates and himself. He believed in its words.

But he did not write the words.

Ahh, yes, history hurts. But I think there might hold a pleasant surprise when I tell you who did write it.

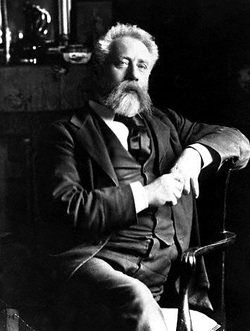

The author’s name is Williams Ernest Henley. Just by the name, you can guess around the era in which he lived. In the 19th century he wrote few poems and was a husband and father before being called an author. His daughter was the inspiration for Wendy in the quite popular book at the time, Peter Pan. As legend proclaims, the bold and maimed pirate Long John Silver was modeled after him in Robert Louis Stevenson's Treasure Planet. A burly, red-bearded man who is described by Stevenson to be "jovial, astoundingly clever, and with a laugh that rolled like music [along with fire and vitality]," William Ernest Henley visibly made a mark in literature. And, notably but not primarily, as that of a disabled Englishman.

Not this John Silver. Though he is intense.

Not this John Silver. Though he is intense. At a young age Henley contract tuberculosis, which resulted in the amputation of his leg from the knee down. It is here, shortly after the procedure, that he penned his austere poem, “Invictus.” I love this poem. It exudes defiance and strength and is the hidden mascot of disability, the unsung testament in our sacred text. But poetry, like any other art, is subject to interpretation, which explains so tenderly why an inmate may be inspired by it as much as Henley’s fellow handicapped should be.

The point of this post is not to lecture you in history, though I’ve confessed already to loving the topic (how many Hail Mary’s is that penance?). The point is to illuminate to all of us that our battle – whether disabled or not, the one that you scowl towards every morning when something hurts or feel a rush of bitterness at insolent misunderstandings – is not a new battle.

Actually, the battle has thawed. The war, though still irrefutably being waged, has turned.

Imagine the suffering of poor medical treatment, unmotorized transportation, injury to the revered masculinity (or feminine expectancy) of the Victorian age (which, I might add, has not become extinct today). You think that’s bad and imagine it in the Middle Ages. Unless you were of nobility, apt to be cared for, what choice did the common man have but to attempt their best with a disability or a disabled family member? I do not believe they were naïve. Yes, the more suspicious or uneducated might have tried to parry their newly-abandoned pagan roots in thinking it a cursed punishment rather than biological twist. But most, I think, were strong and silent, willing but weary, knees-sore-from-prayer caretakers of the afflicted or afflicted themselves.

It has never been easy. Disability is not new. Hurt is ancient. And as I always preach, the most courageous triumphs over the challenges have perhaps not been recorded to the scholar’s eye. After all, that is why it is deemed "his-story."

We are lucky today. We are blessed. I wake each morning and think – in theory, I admit – of how predestined it must be that I was born in this generation. That the world has evolved and locked hands to care for me in ways unimaginable centuries – and even decades – ago. But even before, even when that war was bloody, their heads were unbowed.

So must ours be.

My friends, find me unafraid.

S

P.S.I thought this comic went along perfectly:

The point of this post is not to lecture you in history, though I’ve confessed already to loving the topic (how many Hail Mary’s is that penance?). The point is to illuminate to all of us that our battle – whether disabled or not, the one that you scowl towards every morning when something hurts or feel a rush of bitterness at insolent misunderstandings – is not a new battle.

Actually, the battle has thawed. The war, though still irrefutably being waged, has turned.

Imagine the suffering of poor medical treatment, unmotorized transportation, injury to the revered masculinity (or feminine expectancy) of the Victorian age (which, I might add, has not become extinct today). You think that’s bad and imagine it in the Middle Ages. Unless you were of nobility, apt to be cared for, what choice did the common man have but to attempt their best with a disability or a disabled family member? I do not believe they were naïve. Yes, the more suspicious or uneducated might have tried to parry their newly-abandoned pagan roots in thinking it a cursed punishment rather than biological twist. But most, I think, were strong and silent, willing but weary, knees-sore-from-prayer caretakers of the afflicted or afflicted themselves.

It has never been easy. Disability is not new. Hurt is ancient. And as I always preach, the most courageous triumphs over the challenges have perhaps not been recorded to the scholar’s eye. After all, that is why it is deemed "his-story."

We are lucky today. We are blessed. I wake each morning and think – in theory, I admit – of how predestined it must be that I was born in this generation. That the world has evolved and locked hands to care for me in ways unimaginable centuries – and even decades – ago. But even before, even when that war was bloody, their heads were unbowed.

So must ours be.

My friends, find me unafraid.

S

P.S.I thought this comic went along perfectly:

RSS Feed

RSS Feed